The renjollen had a deep influence on the rigs we use, and the way we sail. They played a major role in encouraging serious systematic study of the way of a boat in the wind and sea, and many of the basic ingredients of the modern boat were developed in renjolle or by former renjolle sailors.

Renjolle racer Manfred Curry, who was born in America but spent most of his life in Germany, has gone down in history as the man who brought science into sailing. At a time when tuning and design were often rough and ready skills based on experience and the seat of the pants, Curry strove towards scientific study and explanation. Many agreed with New Zealand’s Peter Mander (who won a gold medal in a renjolle type in the 1956 Olympics) when he wrote that Curry’s work was “the basis for all subsequent writings on the subject”.

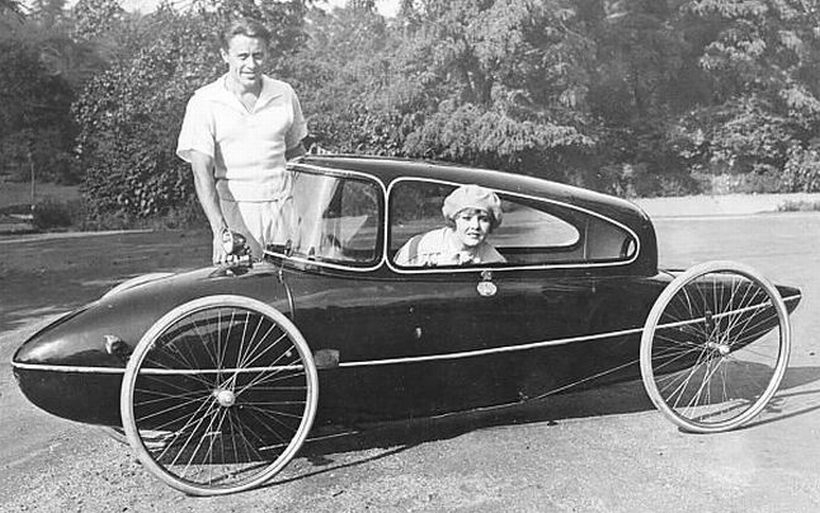

Like many of the great names of the early dinghy scene, Curry seems to have been a renaissance man. He studied nature, examining birds and their wings, the streamlined shape of ice floes on rivers and other free-flowing forms. A skilled photographer, his quest for knowledge lead him to create a book of nothing more than photographs of the natural effects of light, wind and waves on sea. Curry’s fascination about the flow of fluids even extended to his creation of the “landskiff”, an efficient streamlined recumbent four-wheeled bicycle.

But for his studies in the workings of sails, Curry also moved away from observations of nature and adopted the newest technology of the day. He set up model rigs in the wind tunnel of aircraft designer Dr Hugo Junker (of “Stuka” fame) and took photos of smoke streaming over tin sails. He burned smoke pots aboard renjolle and photographed the plumes as they blew past the rig. He probed the mystery of the boundary flow by stitching tufts to sails; standard today but a new idea at the time. He advocated the genoa jib, and claimed to have invented it (as do Sweden’s Sven Salen and Francis Herreshoff).

Influenced by traditional rigs from India and Chinese junks, Curry started experimenting with long battens in 1922. Within a few years, he claimed, sails with 14 or more battens were popular in the renjolle, although given that canoes had used them in the 1800s Curry’s exact influence is unclear. In those days, though, long battens were fragile and heavy, and had to be removed after each sail. Their weight and inconvenience lead to them dropping from favour in the northern hemisphere for many years, but the reminiscences of men like England’s Austin Farrar, a very influential sailmaker of the 1950s and 1960s, leave no doubt that it was Curry’s influence that kept full battens alive in classes like Canoes long enough for them to return to favour in catamarans and then other classes.

Many of Curry’s ideas found physical expression in his renjolle. Fascinated by cleaning up the airflow over the sails, he experimented with a bi-pole mast system, and adopted a low and streamlined design with a curved sheer and gunwales to allow a cleaner airflow over the feet of the main and jib. He appears to have developed the cam cleat in its modern form; a step on from the lever-operated cam of Paul Butler. He created gybing centreboards and lightweight fittings in aluminium- an exotic materials in the days. Curry’s boats had everything – even brakes. A pair of foils projected astern of the transom and could be dropped into the water to slow the boat at starts and mark roundings.

Curry was a skilled sailor as well as a theoretician. It’s said that he won over 1000 races in Germany, and he finished mid-fleet when he sailed 8 Metres and International 12s for the USA in the 1928 Olympics. Curry’s writings on racing tactics are still often valid today; for example, as early as the 1920s he set out in some detail the concept of tacking downwind.

But there’s another side to Curry’s story. Some great sailors believed that Curry tilted his experimental results to back up his theories (and he’s not the last in the field to suffer that charge). L. Francis Herreshoff went as far as calling Curry a “myth lover” and claiming that his renjolle designs were uncompetitive. Tony Marchaj, a leading sailing scientist of a later era and a qualified aerodynamicist, was scathing about Curry’s lack of scientific grounding; basic theories, like the concept of induced drag, “incorporated in every classic textbook on low-speed aerodynamics were unknown to Manfred Curry” he wrote. Curry’s ideas of the basic mechanics that allow a boat to sail to windward “contradicts elementary principles of mechanics and of aerodynamics…” claimed Marchaj, who labelled Curry’s wind-tunnel as “amateurish”.

There are other flaws in Curry’s claims to scientific credibility. He became an advocate of the discredited “science” of physiognomy; the belief that personality could be judged by facial structure. Among water diviners and dowsers and other followers of alternative medicines, he is revered as the “discoverer” of “Curry Lines”; lines of “geo electricity” that somehow find their way up from the bowels of the earth but can be diverted byt moving a stone, and remain mysteriously hidden from physicists and their instruments. He apparently also promoted the existence of “Aran”, a “heavier form of oxygen”. Curry’s claims to have brought science into sailing should perhaps be judged against his claims to have discovered geomagnetic faults that can only be found by believers armed with divining rods.

There is sadness in the tale of this brilliant man. The “authorities” about Curry Lines whom I could contacted know nothing of his sailing career. The lakeside medical institute he founded now lies in ruins. Curry possessed many talents, but perhaps the ability to separate fact from fiction was not among them.

But in the end, for sailors the problems with Curry’s science may seem minor compared to his contribution to the sport. He inspired designers such as Ben Lexcen, of America’s Cup fame, and many sailors. As Frank Bethwaite wrote, Curry’s books helped to create a fundamental change; “the technique of sailing ceased to be a mysterious art….Curry explained a logical technology (which) could be discussed with others in a common language”.

Perhaps nothing shows the problems of do-it-yourself aerodynamics better than the story of another German dinghy sailor of the same era. Like Curry, he was ignorant of the established aerodynamic theories. In 1914, he decided that simply applying the theory of the Swiss century mathematician Daniel Bernoulli would create the perfect wing section. When his theory was put to the test, the plane barely flew and the test pilot barely survived. “That is what can happen to a man who thinks a lot but reads little” noted the sailor later. His name? Albert Einstien.

Dinghy sailing was one of Einstien’s greatest passions. When he first discovered the sport he would take an uncomfortable Marie Curie out on Lake Geneva in a small dinghy; two of the world’s greatest minds adrift in a cockleshell. He sailed through heart problems until his doctor ordered him ashore, and graduated to a “Jollenkreuzer” or dinghy cruiser – basically a renjolle with a cabin. When he moved to the USA his greatest pain was to leave his beloved “Tummler” behind, but he found solace in sailing unpretentious little boats.

Some photos show in a nondescript boat that looks like a hard chine design, but others speak of him sailing an 5.5m/18’ Cape Cod Knockabout. “He was crazy about his little sailboat” a neighbour later recalled. Sailing became his way to fleet from fame; “whenever Einstein spotted a stranger’s car coming up the drive to his summer home, he escaped in his sailboat”, until his wife complained that he could never be found ashore.

Einstein was no racer. He may not even have been much of a sailor. He never made any great contribution to the sport. But he showed that dinghy sailing could be a source of never-ending delight to the most brilliant of humans. He also showed that even the greatest of scientific minds cannot always understand the theory of sailing.

But while Manfred Curry and Albert Einstein were floundering in their attempts to understand the science of aerodynamics, the men who sailed the renjollen were making great strides in a more pragmatic approach to sailing. For many early dinghy sailors, “tuning” was simply adjusting rake and making sure the stick was straight. But the sophisticated renjolle sailors were keenly interested in development. Sailors in boats like the Z Jolle and H Jolle crafted lightweight hollow masts, gaffs and booms, and ended up with gaffs that bent like a modern flex-tip rig. Sailors in classes like those in the H Jolle and 12 m2 Sharpie played the gaff like a modern downhaul, allowing the head to drop aft and to leeward to depower.

One of the renjolle sailors who were familiar with bendy gaffs was Walter Von Hutschler, Brazilian by birth but German by descent and residence. When he moved from the H Jolle fleet to the International Star class, he seems to have taken his experimental attitude with him. He shaved away at his boom until it bent to so that the “foot of the mainsail conformed to aero‑dynamic principles more so than when a rigid boom was used…”. Perhaps inspired by his background in the efficient and development-minded renjollen, Von Hutschler saw further development avenues. “This experience led me to try to apply similar conditions to the mast. By tightening or loosening the shrouds, (upper, middle, and lower) the mast would bend and by doing so, it vitally improved the aero‑dynamics of the mainsail” he wrote. Von Hutschler’s technique made him dominant in the Star class and launched the bendy mast into the sailing world. There is little doubt that the Star class was the test-bed for this huge leap in sailing techniques, but it also seems more than a coincidence that it was created by a former renjolle sailor.

“He was crazy about his little sailboat”: – p 280, “Einstein, a Life”, Denis Brian, John Wiley & Sons Inc, 1996.

“He may not even have been much of a sailor:” – see for example Brian p 262-3, although some sources speak of him as an excellent skipper.

A great article Chris! Nice seque to Einstein.

There are have some articles published about Einstein’s sailing in mainstream sources.

MIK

LikeLike