In 1949, on the crux of the dinghy boom, an amateur created a boat that would would raise the standard and profile of dinghy sailing and become the greatest of all Olympic dinghy classes. It was the Olympic Finn, and although in some ways – its construction, its weight and its method of creating stability (good old-fashioned gut-busting hiking) – it was similar to pre-war boats, in other ways the Finn was the precursor of the dinghy boom that would make sailing into a popular sport.

The Finn story started when five men sat down to create the criteria for a design competition for the Finnish Yachting Association. They were looking primarily for a boat for inter-Scandinavian competition, and only secondarily for a singlehander for the 1952 Helsinki Olympics. Like most European boats of the day, the new singlehander had to be suitable for cruising as well as racing.

In a move symbolic of a new internationalism in the sport, the Finns had handed over the selection of “their” class to the Swedes, the accepted leaders of Scandinavian dinghy sailing. The boat that the Swedes chose as winner of the design competition was a boat called Spicle, designed by professional naval architect Harry Karlsson and similar to the classic British dinghy style. Spicle was a flawed concept as a singlehander, a winner only on paper, but by looking at her we can see what made the Finn so special.

While Spicle was being touted as the new Olympic class, Sweden’s Rickard Sarby had been developing a design from a much older heritage. Sarby had finished fourth in the singlehanded Firefly in the previous Olympics, but he had come from the canoe classes that dominated Swedish centerboard sailing. The Swedish canoes, which still survive in smaller numbers, are substantial cruiser-racers up to 6m long and 1.75m in beam. They look more like expanded versions of 1890s canoes than the slender ICs. But they were highly developed and fast, and Sarby had already shaken them up when he introduced a lighter, flatter-sterned planing hull. He was so concerned with saving weight that he actually reduced overall length, something which is anathema to most designers. Sarby’s home-built designs were so successful that boats like his 1949 E Class canoe “Schock” were still racing at national level into the 21st century, and his reputation was so strong that he was one of those chosen to create the specifications for the new singlehander.

Despite his success in canoe design, Sarby was still a barber – a common working man, at a time when dinghy sailing in Sweden was a rich man’s game. There is a legend among some Finn and canoe sailors that he did not know how to draw plans and could not afford to have someone draw them for him, so he did his designing with a saw. “The story was that one day Richard went down to his shop and cut off the pointy stern of one of his C-canoes and also removed the mizzen mast” says one of Sweden’s top Canoe sailors “I have seen many C-canoes and the older ones bear close resemblance to the Finn. Cutting off the stern on one of those boats would essentially give you a Finn hull.”

The truth according to Sarby is a bit more prosaic. The Finn does look like uncannily like a cut-down C Class Canoe, but Sarby’s account indicates that that the boat was designed with full-size plans (in “the usual canoe manner”) before the prototype was built by Sarby and his brothers while the designer was recovering from losing two digits to an electric cutter.

Fred Miller Jr, a hot sailor in the Finn’s early days, heard a third story which manages to combine the previous two into a plausible tale. “Sarby had some definite ideas, but then (as today) Sarby has been incapable of making a drawing any builder, other than himself, could understand and build to” he wrote. “So, the story goes, Sarby set to building a duplicate hull of his fastest (before or since) boat of the open-design class E sailing canoe. After doing so, making a few minor alterations here and there, he sawed off the last four feet and nailed on a transom…..He went sailing, coming right back in to telephone a naval architect to come up and make a drawing as quickly as possible”.

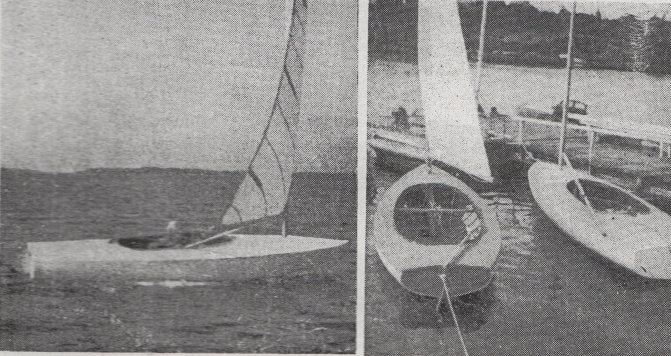

Plans that have recently come to light at the superb Norwegian/Swedish digitalmuseum.org project prove that Sarby could in fact draft a plan, although not to the standards or level of detail of his professionally qualified rivals and perhaps not well enough to give a builder enough information to achieve Sarby’s concept. But however she was created, the Finn would never have become an Olympic fixture if it had just stayed an idea on paper. It failed in the design competition (she looked too small, the judges told Sarby) and Sarby was only invited to the trials when the FYA learned he had already built a prototype. In the light-air trials, the Finn proved competitive with the bigger Spicle, but the old O-Jolle was as fast or faster as both of them. The jury asked for the Spicle to be re-designed, and invited competitors to return for a second set of trials.

Sarby had no intention of participating in the second trials, but the sailors of the middle of the century had an unstoppable urge to build boats. A sailing magazine published the Finn plans, and people were so attracted by the boat and its simple building method that 25 were built over the winter of 1949-50. The popularity of the Finn encouraged Sarby to enter the second trials, and in stronger winds the Finn dominated, scoring five wins and a second. The Finn was declared the new Olympic class, and Sarby himself went on to take the bronze medal at the Helsinki Games. Here, in a nutshell, we can find a pattern of the dinghy boom. If not for those 25 keen home builders, the Finn would not have been selected. All of the best-laid plans of international associations and professional designers were beaten by the popularity of a simple boat that amateurs could build at home.

So why did the hairdresser’s boat beat the professional design? The hull of Spicle (renamed Pricken after being redesigned for the second trials) looks like a standard racing dinghy of 1949 – “not unlike a somewhat elongated Merlin” was one verdict. Her rig is similar to the Finns and the foils are higher in aspect and look more modern.

But Spicle was slow in chop and nosedived. The fatal flaw, perhaps, was the shape of her bow sections. Like many boats of her day, she was very fine and Veed down underneath the waterline, and very wide and flared further up. It is often a lethal combination – too little flotation down low to prevent nosediving, but too much topsides bulk to cut through the waves.

Spicle’s bow shape may not have been a problem in a crewed boat, but upwind grunt is a perennial problem for the hiking singlehander. Although they’ve got most of the wetted surface and weight of a comparable crewed boat, they’ve got about half of the righting moment. Life is even tougher in waves. Planing over the waves upwind is not an option for a hiking boat without wings or trap. Somehow, the singlehander has to punch through the swell and chop.

One of the Finn’s secrets was its long slim, canoe-style bow, which was much narrower than other boats of the time. The widest point of the waterline is well aft. There’s little flare above the waterline for a boat of its age, and the deepest point of the keel line is right forward – further forward, in fact, than any other major class. The Finn’s deep, fine slab-sided bow carves through chop and swell, while its sheer weight gives it the momentum to punch through. As Frank Bethwaite has noted, it performs much better in light airs and waves than any boat of its dimensions deserves to do. The Finn’s bow showed sailors the way to the finer entry of the future.

The plans at the Digitalmuseum.org site show that when he designed the Finn bow, Sarby was following a style he had been using in his canoes. He had also designed a 3.6m long Finn-style in 1944 that had the same sort of fine, deep bow.

For some reason, the Finn missed out on one of the Swedish canoes’ other great assets – the twin pivoting seats that flip out over each gunwale for hiking leverage, like floppy little wings. Ironically, as early as 1967, the class president contemplated fitting hiking seats, pivoting out from each gunwale, to stay competitive with the new breed of trapeze and sliding seat singlehanders. Perhaps it was because of the lack of hiking power that Sarby gave the boat its low-aspect centerboard; it’s not the best shape to prevent leeway, but it is forgiving and has a lower less heeling tendency than a deep foil.

Considering that Sarby introduced the flat “planing stern” to Swedish canoes, the Finn’s stern seems strangely archaic – more like ancient Avenger shape, or a yacht’s. The sterns of the O-Jolle and Spicle look more modern. Sarby had already shown that he wasn’t concerned about getting maximum length. He wrote years later that his main concern was reducing wetted surface, and the Finn’s narrow stern is probably the result. To reduce wetted surface, he designed the boat to sail bow-down, with the transom well above the water and a waterline shape very reminiscent of the Swedish canoes. The Finn didn’t take up its current fore-and-aft trim until construction developments allowed weight savings in the centerboard case and bow.

By modern standards the Finn’s stern helps to make it notoriously hard to handle downwind in a breeze, but Sarby believed that she handled better than the other triallists on the square runs. What terrors they must have been!

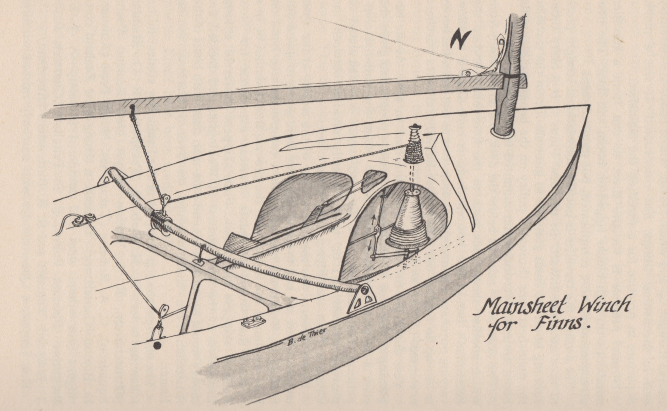

The Finn’s unstayed rig was new to most sailors, who did not realize that the Swedish canoe sailors had already been taking the first steps towards the self-adjusting unstayed rig. In light airs and downwind, when the mainsheet was slack, the mast stayed upright, forcing draft into the sail. As the breeze picked up, the mainsheet was wound in, flattening the cloth. Once the Finn sailors got to grip with the concept, they realized that they could tune masts and sails to match their leverage. They had to- few singlehanded boats without hiking aids have to handle such a big sail. The well equipped Finn sailor spent hours with plane and glue, carving timber off the mast to make it softer or adding slivers to make it stiffer. It was, it seems, the first real example of a rig tuned to the individual’s weight. It was the Finn’s combination of basic simplicity and technical complication that lead Peter Mander, fourth in the 1956 Olympics, to christen it “a diabolically ingenious machine.”

In the early Olympics, though, the Finn was a strict one design as supplied by the organizers and no alterations were allowed. At the time, it was said to be the best way to test a sailor’s skill – although ironically today the powerful Olympic Finn lobby says that its looser one design rules make it a better test of a sailors skill than the strict OD Laser.

Attrbution-ShareAlike (CC BY-SA)

Perhaps, though, the Finn’s greatest influence came not in bow shapes and rigs, but in sailing techniques and standards. At first it was not only the sole Olympic dinghy, but also the fastest and most widespread of singlehanded dinghies. Its dual status attracted a brilliant clan of sailors who set new marks in training, sailing technique and development. They did not have the financial assistance to sail full time like modern Olympians (while Elvstrom sailed eight hours a day before every major event, it was only for the preceding week) but their dedication was the same – Elvstrom and his training partners sailed every Saturday and Sunday through the winter unless there was too much ice, and that was in the days before wetsuits. Others strove to catch up, and the list of Finn sailors include many – Bruce Kirby, Ian Bruce, Peter Mander, Hans Fogh, JJ Herbulot – who were to leave major marks in dinghy design.

The Finn also changed the status of dinghy sailors. Keelboat sailors, especially those in the Star class, had always claimed to be the most skilful of all racers. As Finn Olympian Garry Hoyt noted “the Star class skippers for a long time let it be known, officially and unofficially, that they were the world’s best class with the world’s best sailors. They were sustained in this modest claim largely by the questionable evidence of their own applause…the 5.5’s also picked up this bit, and somehow were able to translate ‘spending power’ to read ‘sailing skill”. Then Finn legend Elvstrom moved from Finns into 5.5s and Stars. First, he won the 5.5 worlds with an old boat. “I heard later that some Star-boat skippers immediately said “There you see what sort of class the 5.5 metre is when a dinghy sailor just can go out and clean them all up. You wait till he gets to the Star class” was the way 5.5 champion George O’Day said it. And what happened when he did? The “dinghy sailor” cleaned up one of the hottest Star fleets ever seen.

“It was with a great sense of vindication that the small-boat sailors of the world saw Paul Elvstrom smite the philistines from their pedestals” Hoyt wrote with relish. “And-oh sweet revenge- he did it to them by frequently employing dinghy tactics like sailing by the lee, and other little peasant pursuits that the aristocrats had missed…”. As a Finn champ, Richard Creagh-Osbourne may have been slightly biased when he said that the Finn was “the design which must have done more to influence boat performance and competition in all racing classes than any other in the history of yachting” – but he may also have been correct.